- Supports

- About

-

News and Events

News and Events

Events

How can we help?

Kings and fat horses: Understanding 3 Ms in Lean

18th

October 2023

By Torbjørn H. Netland

The “3 Ms”— muri, mura, muda — is among the most important concepts in lean production. Yet, the Ms are often misjudged.

The most common misunderstanding is to see lean only as a method to reduce waste (“muda”). Those that start waste-hunting lean projects will not achieve break-through improvements and will never build a culture of continuous improvement. When Toyota developed the Toyota Production System, they learned early on that there are two other enemies of productivity; muri and mura. In my field studies of lean in numerous factories around the world, I have learned that the sequence of the words matter. To efficiently improve a process, muri should be attacked before mura, and mura before muda.

The English translations of muri, mura, and muda as used in a manufacturing settings are well established as “overburden,” “unevenness,” and “waste”. Although this is an accurate translation of the meaning, there is more to it. To learn more about the deeper meaning of the 3 Ms, I sat down with Hugo Tschirky, Professor Emeritus at ETH Zurich and an expert in Japanese culture and management. I was fascinated about what I learned, and would like to pass it on to my readers.

Note that I have not seen this kanji-level explanation of muri, mura, and muda anywhere else before. Also, be aware that interpretations of kanjis differ and that I cannot guarantee that this interpretation is correct. The meaning of a Japanese word is not always related to the meaning of the original Chinese characters. Thanks to Professor Masaru Nakano (Keio University, ex. Toyota), Professor Hajime Mizuyama (Aoyama Gakuin University) and Doctoral Candidate Mieko Igarashi (NTNU) for discussing this post with me prior to publication. All remaining errors are my own.

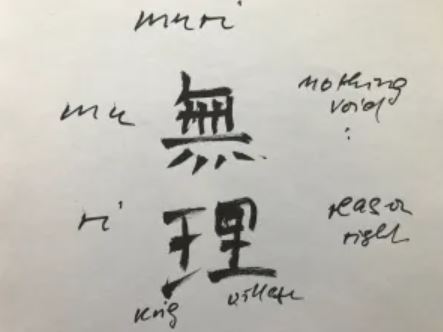

Muri

Muri (無理) consists of two kanjis, which can be translated into “unreasonable” or “’impossible”. The first kanji “mu” (理) shows a fire that burns; it means that nothing is left. The second kanji “ri” (理) illustrates the “king (王) of the village (里)”, which is best translated as “reason” or “correct”. Putting “mu” before “ri”, you get “totally unreasonable”. Hence, muri means something that cannot be accepted. This is a general translation. In a manufacturing factory, we translate “muri” into overburden of machines, people, and processes. Because overload will make the production break down, it is “totally unreasonable”. Muri should be the first thing to reduce.

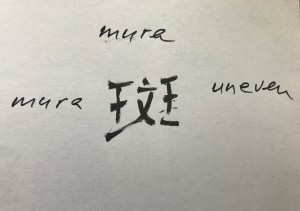

Mura

Mura (斑) starts with the same phonetic sound as muri and muda, but note that its kanji is completely different. It consists of only one symbol that means uneven. There are at least two different interpretations of the kanji itself: It can be seen as a compound of two other kanjis, a simplified version of ? plus 文. ? means two pieces of jades merged together and the 文 in the middle symbolizes a man that have cut them in two dissimilar pieces. Alternatively, it can be seen as a man (文) in the middle of two kings (王), which would symbolize that unevenness is a king-level issue that must be treated seriously. If you have mura in your process, you will get uneven output. Unevenness is the enemy of balance and stability. In a manufacturing setting, it is the second thing to reduce.

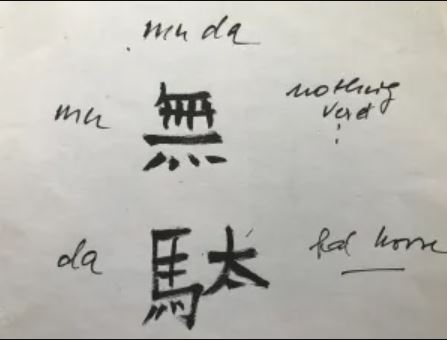

Muda

It is common to translate muda (無駄) into useless, unnecessary, or waste. Muda starts with the same kanji prefix as muri. As explained, “mu” (無) means something similar to “nothing”. The second kanji “da” (駄) consists of “horse” (馬) plus “fat” (太). In the middle ages, horses were of vital importance in the Far East. The horse should be fit and strong. The worst thing you could have was a fat horse. You cannot use a fat horse, yet you must care for and feed it. Note the very common Japanese word “dame” (駄目), which literally means to look (目) at fat horses and is usually translated to “no good” or “don’t do it”. Fat horses are waste and must be avoided, and you should certainly not just stand and stare at them. Luckily, Taiichi Ohno has helped us describe what “fat horses” look like in factories: Transportation, Inventory, Motion, Waiting, Overproduction, Over-processing, and Defects. You must avoid muda, but remember the sequence of muri, mura, muda.

Further reading

- Ohno, T. (1988). Workplace management: Productivity Press.

- For the usual definition of the 3Ms, see LEI’s Lean Lexicon.

- Michel Baudin has several good posts about muri, mura, and muda.

- Prof. Christoph Roser explains the origin of Muri, mura and muda: the three evils of manufacturing.

- Netland, T. H., & Powell, D. J. (2017). A Lean World. In T. H. Netland & D. J. Powell (Eds.), The Routledge Companion to Lean Management, Routledge

This article is written and reproduced with the kind permission by Dr. Torbjørn Netland who is a Tenure Track Assistant Professor and the Head of Chair of Production and Operations Management at the Department of Management, Technology, and Economics, ETH Zurich, Switzerland. You can access his latest content through his website or follow him on LinkedIn and Twitter.